In an effort to provide better hearing health-care, the prestigious National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened a three-day meeting recently. The academy had appointed a committee of 14 hearing professionals, and invited a panel of six patients to testify about their own experiences.

The committee’s mandate is to examine “hearing interventions” in adults, and to establish ways to better measure the results of those interventions. “Interventions” are primarily hearing aids, but the study will also assess the efficacy of assistive devices, auditory rehabilitation, and apps that can aid communication. (Cochlear implants are not part of their study.) The committee will use this information to develop recommendations on how to evaluate outcomes of heaing healthcare, and strategies to develop and adopt new measures. NASEM hopes to publish results in April 2025. Both patients and audiologists are expected to benefit.

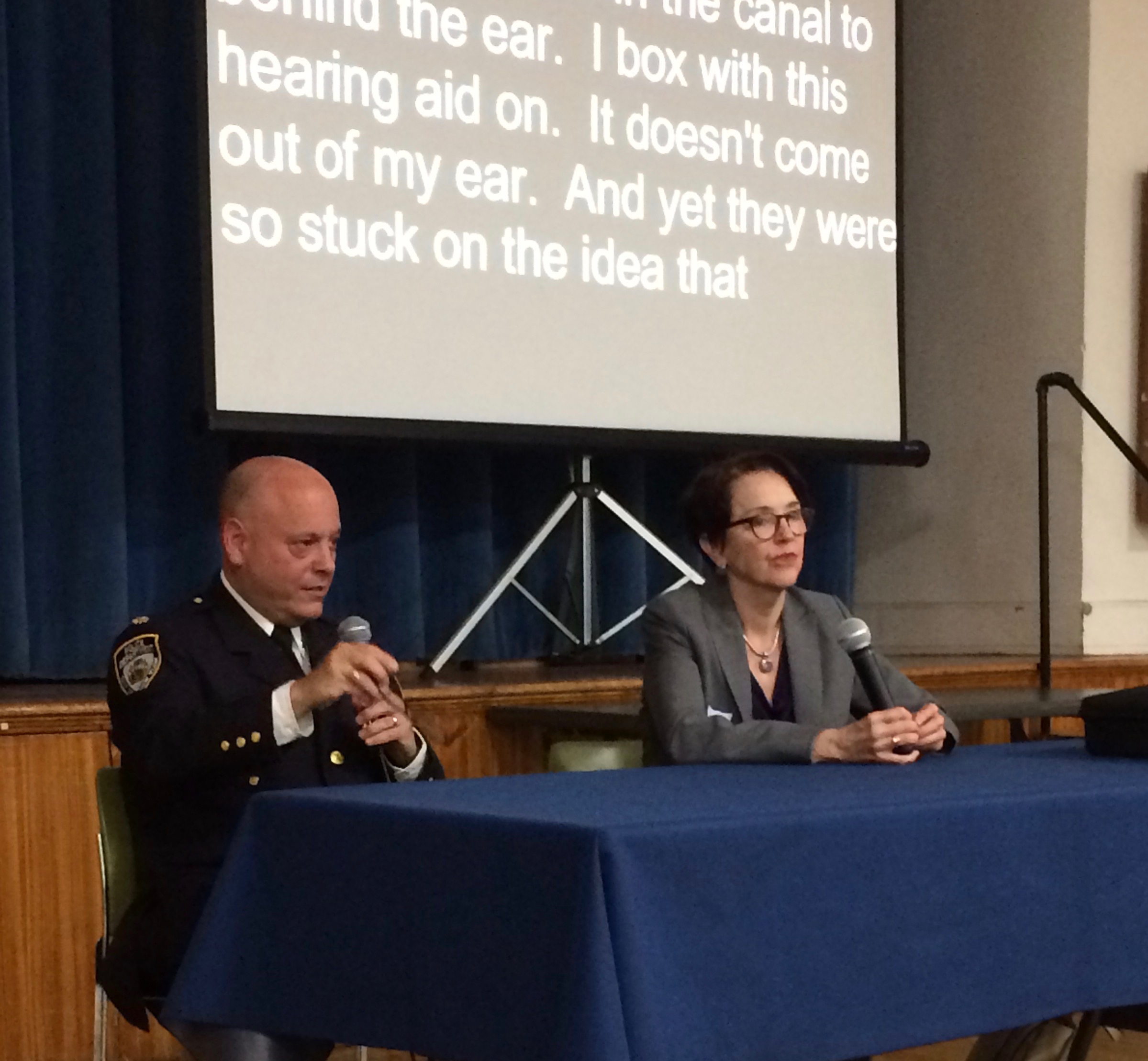

In the initial session, which was open to the public, the patient panel, which I was part of, was invited to talk about what works for them when it comes to hearing interventions, and what doesn’t. All of us were veteran hearing-aid users, and, coincidentally, all active in HLAA. We introduced ourselves and talked about our hearing loss and our experiences with treatment. Inevitably, audiologists were the primary focus.

Audiologists are our most important partners in coping with hearing loss. Many of us have spent years with the same audiologist, getting our hearing tested and retested, upgrading our devices, dealing with technological issues. I’ve been with my current audiologist since 2008, which is a lot longer than many marriages. She’s invaluable, but she’s also very busy, like most audiologists. The NASEM study may help to streamline audiologic care.

The impact of hearing loss on everyday life. We all referred in one way or another to the impact hearing loss had on our work life. Some of us took early retirement because we could no longer manage in the workplace. For some jobs, no existing accommodations would have changed that outcome. Just one person on the panel was still actively in the workplace, and she had altered her work significantly because of her loss. Several panel members said they had not disclosed their hearing loss in the workplace, one adding that she could “never have achieved my potential in a business setting” if she had. Hearing loss impacts on personal life were also noted.

The essential role of assistive devices. All of us use captioning apps and assistive listening devices. Most of us learned about these supplements to hearing aids through informal channels like HLAA meetings and blogs. Audiologists rarely discuss apps and ALDs, including hearing loops, and many still do not activate a telecoil in new hearing aids, which would allow users to take advantage of hearing loops or other systems when they’re available.

Refer patients to support groups, books on hearing loss, and blogs. It’s understandable that audiologists may not have time to supply information like that in the previous paragraph. But why not have a fact sheet for every new patient, with information about groups like HLAA and ALDA, about auditory rehabilitation, about speech reading, as well as a list of devices, apps, and assistive listening systems. Hearing as well as possible often requires more than a hearing aid.

The audiogram vs real-life hearing. We agreed that what sounds fine in an audiologist’s quiet office is often inadequate in the real world. Treat the patient, not the audiogram. Several panelists said their audiologists had never asked them about their lives and their hearing needs. One commented that hearing loss per se is only the tip of the iceberg. Communication should be the overriding goal. For many, hearing aids alone won’t get you to that goal, and audiologists need to understand what other assistance we might benefit from.

The financial impact of hearing loss. In addition to leaving the workplace, with the consequent reduction in income, panelists agreed that hearing loss is financially punitive in other ways as well, primarily because of the high cost of hearing aids and the lack of adequate insurance coverage.

Encourage the patient to be more proactive. No matter how good your audiologist is, the patient’s input is essential. Several panelists said that if they could fine tune their hearing aids themselves, that might work better for them. It’s already possible to choose specific environmental settings and we agreed we’d like to take this a step further. One panelist suggested that an assessment of auditory processing would help an audiologist help a patient in real-world functioning.

The social/emotional aspect of hearing loss. One panelist put it eloquently: “We know that as we develop hearing loss, whether it be sudden or gradual over time, we begin to feel diminished. Suddenly, I have to ask people to repeat themselves. Suddenly, I’m the lesser person in a group. I’m the one who is disabled or differently abled.” This patient was experienced and knew how to advocate for himself. “I knew what I needed to do to enable myself to hear,” he said. “Even so, after you repeat yourself – What? Can you say that again? Tell me what you just said? — after you do that for so long, you just sort of throw in the towel. I’m a good advocate for my hearing, but I understand what people are going through. The social-emotional piece is rarely addressed by audiologists” despite the outsize impact it has on our lives.”

The meeting was on Zoom and was recorded. You can watch it here. You can also submit your own comments for the committee’s consideration.

*

For more about hearing loss, read my books: “Shouting Won’t Help,” “Living Better with Hearing Loss,”and “Smart Hearing,” available at Amazon.com.

Dealing with the stigma of both hearing loss and aging at work can keep some employees from asking for accommodations

Dealing with the stigma of both hearing loss and aging at work can keep some employees from asking for accommodations

me limit.

me limit.