When we talk about hearing loss, everybody benefits, ourselves not the least. This was the message of the January New York City Chapter meeting of HLAA. As President of the chapter, I facilitated the discussion, and it was really great! So many interesting voices, sharing stories of challenges and successes.

Like many people with late-onset hearing loss (mine started when I was 30), I didn’t talk about it for years or, when I did, I minimized it or made a joke about it. That caught up to me, of course. As the loss got more severe, I continued to make jokes. But they fell flat. Even if people didn’t know I had hearing loss, they did know that something was wrong. But not exactly what it was. Dementia? Was I just plain rude? Bored, burned out?

Obviously I didn’t want to seem demented – or any of those other things. When I finally started talking openly about my loss, it was a huge relief, to others as well as to myself. But there’s another benefit of honesty about your hearing.

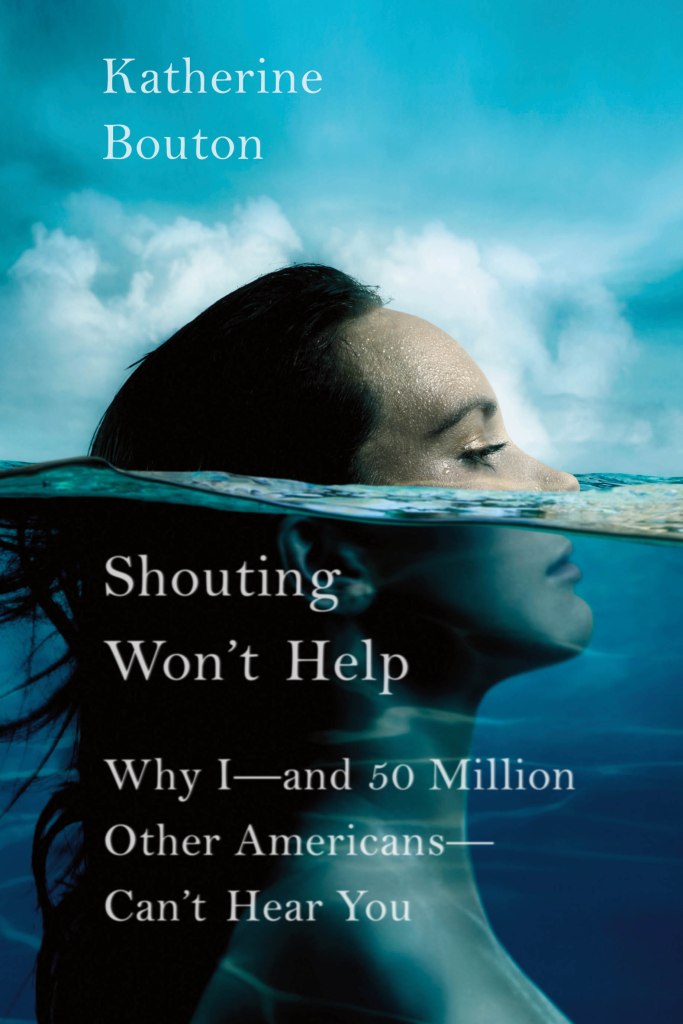

Once people know what the problem is, they try to help. Sometimes you have to guide them to the appropriate way to help, but most are more than willing. They need to speak slowly and in a normal voice. Shouting won’t help, as the title of book says. They need to look at you, so you can read not only their lips but their facial expression and body language. They need to be willing to repeat what you missed. And you need to know the most effective way to ask them to repeat (be specific about what you missed).

The pandemic was especially difficult for those with hearing loss, because we lost a vitally important visual component of speech: the ability to speech read. But it also forced me — and many others — to become more of an advocate for myself. Now I talk about hearing loss all the time.

Doctors’ offices are a good example. Even before masks, a visit to the doctor could be a challenge. I remember one occasion when I had to go to the ER with a dog bite (not my dog!). It was a large urban ER and I couldn’t hear a thing. I just held out my hand and let the doctor take care of it. Even today when I am asked “Date of Birth?” I always stumble. But I quickly pull out my iPhone and the Otter app, and from there on communication is easy.

At first there was resistance to captioning apps like Otter, Google Live Transcribe, Dragon and others. Medical personnel, especially among assistants and receptionists, worried that captions violated HIPAA regulations. Nurses and doctors were more receptive, and sometimes downright enthusiastic. “Cool, how does this work?” It was a relief to them too to know that I heard what they were saying.

The theme of our January HLAA-NYC chapter meeting was self-advocacy: Living with Hearing Loss: Challenges and Successes. At the start of the meeting, I asked people to consider these four questions:

- What was the biggest challenge you faced with your hearing loss, and how did you overcome it?

- Have you made mistakes in your hearing journey, and how did you correct them?

- Where have you encountered the most obstacles in terms of accessibility?

- Has your hearing loss led to unexpected rewards?

Click here to see a captioned video of the program. You can also see descriptions and links to future meetings on the website. If you’d like to share your own challenges and successes, please comment below.

*

You can also read my books: